The Microgravity Team at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln is making strides in producing technology to aid in the health of astronauts – and NASA is taking notice.

The team, which is a part of UNL’s College of Engineering, has been working on a non-invasive method of detecting and monitoring human vitals by means of a swallowable pill. Astronauts are currently required to wear a series of cables and wires, which limit their mobility. A team of eight plans to test the pill in May at NASA’s Microgravity University in Houston to see how it holds up in a weightless setting.

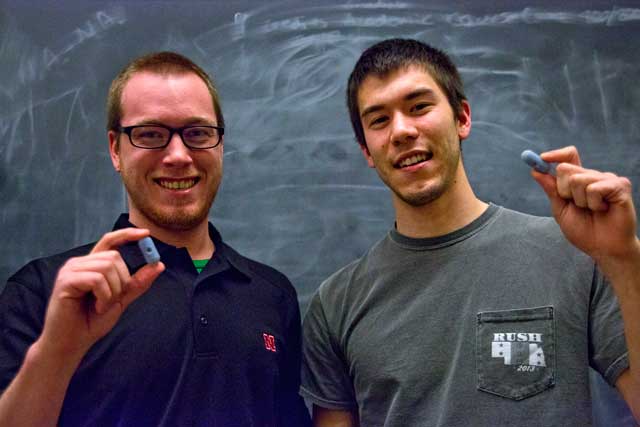

Piotr Slawinski, leader of the microgravity team, said research for the project began about two years ago when he was an undergraduate student at UNL.

“I had been working on the project with Professor (Ben) Terry for a long time,” said Slawinski, a mechanical engineering and applied mechanics graduate student. “We realized one of its applications might be able to be used for zero gravity.”

After graduating from the university in December with a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering, Slawinski put together a team of undergraduate students with the help of Terry, an assistant professor of mechanical and material engineering at UNL.

The team’s job is to figure how to make the device work in outer space. Before testing it in zero gravity with NASA, the team first had to determine whether it worked at all. Before testing the device on humans, it had to be tested on animals, namely pigs.

The device is swallowed by the pig and ends up in its small intestine. The pill, made of plastic and stainless steel parts, attaches itself with tiny teeth to the intestine. Only the inner part of the capsule remains attached to the intestine, while the outer shell travels through the rest of the body.

After the pill leaves the pig's body, a non-survivable exploratory surgery is performed on the pig.

The team came up with a more cost-effective way to test the pill without having to kill a pig to do so.

Terry said the team now uses discarded tissues from local abattoirs, or slaughterhouses.

Using intestines from the pigs, the team came up with a machine that contracts them to make them behave like live intestines.

“The machine kind of brings it to life,” Terry said.

Slawinski said the team uses two tall pressure vessels to cause the contractions of the intestine.

Once attached to the intestine, the sensors may be able to be used to monitor things like blood pressure or temperature.

Terry compared the pill to a space shuttle, in that the pill is simply the carrier and detaches itself from the sensors. He said this could lead to more advanced ways of monitoring health issues, such as diabetes.

Terry said it may be possible to attach a blood glucose monitor, which would allow for virtually invisible diabetes monitoring.

The sensor still has a ways to go before it’s used by humans. One thing that needs to be changed is the size of the pill. At about 18 mm wide and 28 mm long, Terry said it’s too large for a human to swallow.

“It’s fine for the pigs, but not for people just yet,” he said.

The current pill only remains attached to the intestine for about two weeks – Terry said he would like the pill to last for an indefinite amount of time.

Two other universities, the University of Colorado Boulderand Vanderbilt University, are currently working on a similar pill system, one that could perform minor surgeries in a non-invasive way. Colorado, Vanderbilt and UNL are working in collaboration on the projects. Terry said the other pills would have collapsible legs that would let it travel around the body while being controlled by a surgeon.

Eight students and Terry will leave in May to test the pill at NASA’s zero gravity facility in Houston. After that, the team will have to write a summary report during the summer.

“We’re going to see a new space-age where travel times will be a lot longer,” Slawinski said. “It won’t be like the ’70s or ‘80s. It will probably be year-long and this equipment could help a lot. “

As for when the technology will be ready for human use, it could be years, Terry said.

“Technically speaking, it could be ready in two years,” he said. “But in reality, it will take much longer.”

The first trial test on the pig intestine was only last week, so human clinical trials probably won’t take place for about two more years. After that, Terry said there could be multiple possibilities as to what to sensors could be used for.