The coronavirus pandemic has dealt significant blows to state economies across the United States, especially in places like Kentucky, Hawaii and Georgia.

But in South Dakota, Utah and Nebraska, unemployment claims have been far more muted.

In all three states, initial jobless claims from March 14 through May 2 were less than 11% of their respective March labor forces. Those were the lowest rates in the country. Some of the contributing factors include a diverse mix of industries, low jobless rates before the crisis and stronger state budgets.

“Macro economists, we tend to homogenize the states,” said Joseph Santos, professor of economics at South Dakota State University. “The reality is the experience that a state has with a business cycle could be a lot different from one state to the next.”

South Dakota

South Dakota’s economy had fared “rather well” during the economic expansion, Santos said. Prior to Covid-19, unemployment levels were consistently low.

“We were hovering in the 3-somethings for quite some time,” he said, referring to the state’s unemployment rate, which is measured through a survey of households “I’m guessing, relative to our history, we’re going to see something quite dramatic in April.”

During the seven-week period from March 14 to May 2, a total of 37,645 South Dakotans filed initial claims for unemployment benefits, representing about 8.1% of the March labor force, according to Department of Labor data released Thursday. It’s the lowest rate of initial jobless claims of all 50 states.

A possible explanation is the mix of dominant sectors: education and health services; government; and trade, transportation and utilities, Santos said. The state also has a robust financial and community banking industry, spurred in part by usury law changes that eliminated the caps on interest rates and attracted the likes of Citibank and other credit card issuers.

A noteworthy caveat, Santos said, is that the initial claims data is non-farm, and agriculture and related industries are a crucial element to South Dakota’s economy.

Prior to the pandemic, South Dakota farmers and ranchers were navigating challenges caused by forces such as drought and a trade war. Now, they’re dealing with weak commodity prices in corn, soy beans, hogs and cattle, Santos said. On the processing side, South Dakota is home to a Smithfield meat processing plant that last month became a coronavirus hotspot.

“There’s a lot of concern about the agriculture economy,” Santos said.

The concerns extend to whether the state will see a disruption in the summer tourism season, Santos said, noting attractions such as the Black Hills and Mount Rushmore will likely draw fewer visitors.

“Through the summer, if leisure and hospitality services cannot do what they’ve done in other summers, I suspect you’re going to see a dramatic effect on the state’s economy,” he said.

Utah

Utah has been fairly insulated from the brunt of the economic pain.

“[Utah] entered this crisis very well-positioned,” said Natalie Gochnour, associate dean at the University of Utah’s David Eccles School of Business.

Utah’s unemployment rate was 2.5% heading into mid-March – the lowest in state history, she said. The state also had just come through its longest-ever economic expansion, a decade-long period that saw a significant amount of job growth, low unemployment rates and a substantial diversification of the state economy.

The 145,743 initial claims in the seven-week period represented about 9% of the state’s March labor force, according to Labor Department data.

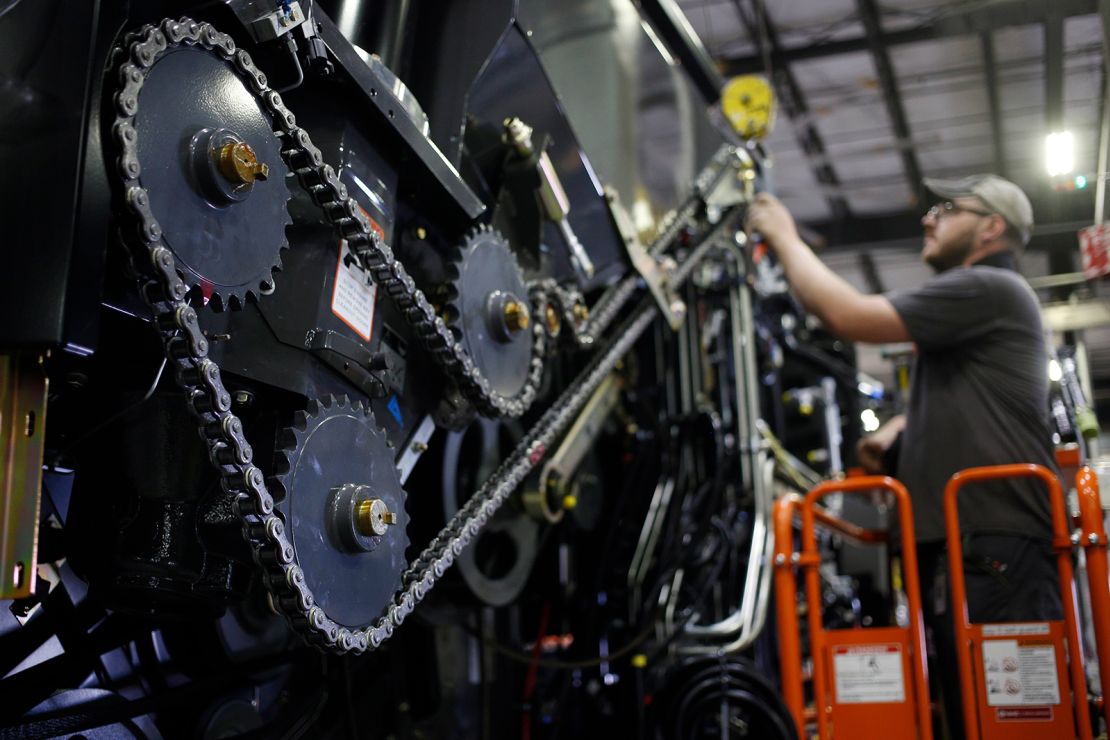

Long a goods-producing state home to Kennecott Utah Copper and a former Geneva Steel mill, Utah’s industry mix now spans manufacturing, energy, technology, outdoor products, defense, aerospace and agriculture.

The state’s interior Western US position makes it a hub for warehousing and distribution industries that have been in high demand in recent weeks. The state’s network of health care businesses serves Utahns in addition to people from southwest Wyoming, southeast Idaho and northeast Nevada, she said.

It helps that the state has a more than $800 million war chest for rainy day funding as well as plans to mitigate economic losses and increase coronavirus testing, Gochnour said. It also has a $4.1 billion public works project at the Salt Lake City International Airport, which has “kept people in place and at work.”

“We’re fortunate to be in a state where we’ve had all those things,” she said. “We don’t take any of them for granted.”

Nebraska

Entering the pandemic, Nebraska was doing OK, for the most part, said economist Eric Thompson, director of the Bureau of Business Research at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

The farm sector had its challenges, especially during President Donald Trump’s trade negotiations with China, but the overall state economy, in terms of wage growth and job growth, were chugging along, albeit growing at a slower pace than the nation, he said.

“The [Covid-19] impact here has been significant,” he said. “But that might be about half as large as nationwide.”

During the past seven weeks, 110,764 Nebraska residents filed initial claims for unemployment benefits, or about 10.5% of its March labor force, according to Labor Department data.

“I think what we’re seeing in Nebraska is fairly typical of states like this,” Thompson said. “Our economies are being hit hard, but not as hard as the rest of the United States.

As with South Dakota, the initial claims data doesn’t reflect the impact to farmers and ranchers, which account for about 5% of the state’s jobs.

Other primary industries include a large rail and trucking sector; farm equipment manufacturing; insurance; and finance.

“These are necessities that obviously are needed throughout the business cycle,” he said, noting that the concentration of insurance and finance industries mean a large subset of people have jobs that are feasible to work remotely.

In the coming weeks, Thompson plans to keep close watch on the continuing claims.

“I do wonder if other parts of the country might bounce back a little more quickly than we will,” he said, adding that loss of economic activity elsewhere is linked more to state-mandated shutdowns and stay-at-home orders. “They’ll snap back. More of our loss simply reflects wariness on the part of consumers and business owners.”

– CNN Business’ Annalyn Kurtz contributed to this report.