Farmers of old wore the signature straw hats and bib overalls. If the University of Nebraska-Lincoln (UNL) completes its mission to grow plants in space, future agriculturalists may be sporting space suits and moon boots.

SPACE2: Space, Policy, Agriculture, Climate and Extreme Environment is the audacious vision of a group of 18 UNL faculty and research members to lead the nation in planting the first acre of corn or soybeans on Mars. They project that within the next half century, agriculture will be necessary for human survival in outer space.

“Looking into the future, if we are to have human settlement on Mars or the moon, particularly to sustain long-term exploration or living there, a lot of science technology has to be done. Agriculture is part of it,” said Dr. Yufeng Ge, professor of biological systems engineering at UNL.

Ge is principal investigator of the SPACE2, along with Dr. Santosh Pitla, associate professor of biological systems engineering. They share a common goal with individuals at other college campuses in Nebraska, as well as a host of other land-grant universities, to sustainably grow food in space. Ge said they have discovered quite a bit of activity happening in public research institutions but on an individual level with small-scale projects.

Ge said that no other university in the United States has a program specifically dedicated to space agriculture. SPACE2 is shooting for the moon so that UNL will become the first.

SPACE2 introduced the idea of blending agriculture and space last November at the Ag4Space Symposium.

“That was the first time ever at UNL for Ag4Space. We invited NASA, USDA, research institutions and industry representatives,” said Ge.

The SPACE2 initiative joined Ag4Space as part of a larger, national movement called “Find Your Place in Space.” In conjunction with the solar eclipse on April 8, the week of April 6-13 was formally recognized by the Biden-Harris Administration as “Find Your Place in Space Week.” More than 235 space exploration events were held across all 50 states, including an “Ag4Space” open house on UNL campus April 9.

During the open house, UNL students and faculty shared research they are doing involving agriculture in space, including drone technology, autonomous implements, soil remediation and plant genetics.

Nebraska Extension also provided hands-on activities at the open house to engage with youth. Participants were encouraged to match personal attributes with a career that may lead to the space industry. Most of the career choices, like a farmer, nurse, communications specialist or physical trainer, are a little alien to the mainstream concept of occupations in space.

“We want to broaden people’s understanding of how they can play a role in space exploration, because it’s a lot bigger than just being an astronaut and going to the moon,” said Dr. Jenny Keshwani, associate professor in biological systems engineering at UNL and education outreach lead for Ag4Space.

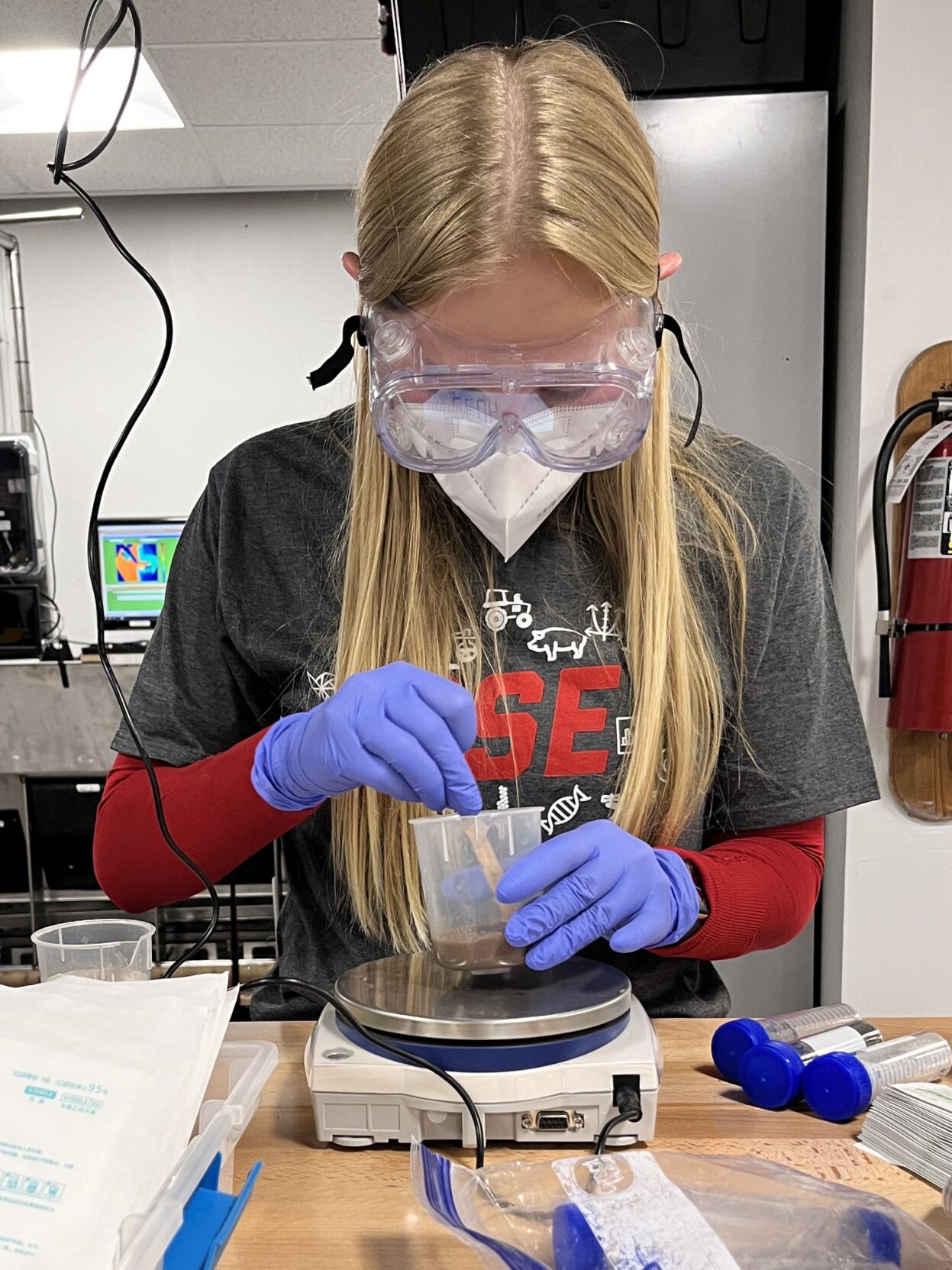

Cassie Palmer wears safety equipment while preparing experiment materials. Much of her work within biological engineering focuses on agriculture in space.

If growing plants in outer space seems “out of this world,” prepare yourself for takeoff as we countdown the work already been done to form settlements beyond Earth.

Ge said that NASA plans to decommission the International Space Station (ISS) within the next five years or so. The idea is to replace the one integrated ISS used by the entire world with smaller platforms that can orbit independently.

“We envision in the future that these settlements will be a couple hundred people, and they need to eat,” said Ge.

These people would be responsible for scientific exploration and maintenance of scientific equipment. Producing food would be a secondary priority for them but likely necessary as deployments into space get longer.

“You may be away from Earth for six months, or if you travel to Mars, a one-way trip is eight months. The launch window is every 26 months—you have to foresee that you will be away from Earth a long time before you can come back,” Ge said.

This is where Nebraska agriculture collides with space exploration. Those involved in SPACE2 believe that Nebraska will be instrumental in the future space race because of the agricultural research already being conducted here in the heart of the Corn Belt.

“We really think Nebraska can play a major leading role in the intersection of agriculture and space,” said Ge.

Producers in the Midwest have certainly proven that they can transform a desolate prairie into bumper crops. However, the volatile climates and unforgiving environment of the celestial bodies pose a unique set of challenges when trying to grow crops in outer space. Nebraskans may joke about having four seasons in one week, but that pales in comparison to the temperature extremes on Mars of 70°F in the daytime and -128°F at nighttime in the summer, according to Space.com. Then there are differences in gravity, atmospheric pressure, gases, radiation and other hazards.

One experiment compares plant growth in soil from earth, Lunar highlands simulant and Martian global simulant. If soils from other planets can support plant growth is a question researchers are trying to answer.

The soil itself on Mars is unfertile for growing plants, even toxic. Doctoral student Cassie Palmer explained that the Martian soil has high concentrations of perchlorate compounds. Consuming food grown in this type of landscape has the potential to destroy lymph nodes and thyroid glands, she said. However, introducing microbes may help remediate the soil.

“Microbes don’t require much food or energy, and they can transform perchlorate into oxygen, water and chloride ions,” Palmer said.

To help people at the Ag4Space open house visualize the limitations of growing plants in extraterrestrial soil, Palmer had brought a tray of seeds planted into three different soils: normal earth, Lunar highlands simulant and Martian global simulant. All were sourced from the Earth, but the rocks were carefully selected to match mineralogical data and ground to the correct particle size.

The experiment revealed no growth in Martian soil. Seedlings had emerged in the Lunar soil, but growth was stunted compared to the earth seedlings. Soil additives and a controlled environment would likely be necessary to grow plants in space.

“The goal of working with plants in space and using soil is to transform the rocky, dangerous soil and find a way to cycle nutrients in the system,” Palmer said.

Hydroponics or aeroponics may be options for growing plants, but the goal is to grow plants on a larger scale within the soil. This is because crops are desired not only as a source of food but also fuel.

“Hydroponics usually grows leafy greens. The soil can support more diversity to grow vegetables or soy—these byproducts can be used for fuel purposes,” Palmer said.

Youth were encouraged to “Find Your Place in Space” as they investigated future careers in the space industry.

Colleagues from other institutions are conducting similar experiments with their own research projects. Ge revealed how the University of Minnesota is exploring soil remediation, whereas the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign is designing greenhouses to provide a controlled environment. The University of Colorado Boulder is developing a growth chamber to optimize gas compositions and lighting conditions to promote the growth of plants, both while being transported during a space flight and maintained for a prolonged period at the space station.

An in-depth analysis of plant genetics is another aspect of future research for agriculture in space. The type of plant and hybrid selected will depend greatly on what can grow in outer space. Keshwani said that different types of plants will be studied for drought resistance and cold tolerance, both climate extremes experienced in space. Then there are the unknown components of plant growth, such as if certain conditions on the moon or Mars could reinvigorate genes “silenced” by the Earth’s atmosphere.

Specialized equipment will also be needed to grow crops in space. Gravity variances on the moon or planets will affect the planter’s downforce and, consequently, seed depth. Moreover, implements will have to be small enough to fit in a rocket ship.

Autonomy will be key.

“Agriculture and plant production will be very important, but I emphasize the need for automation. The people need to eat fresh food but shouldn’t have to worry about planting or harvesting,” Ge said.

Automation will be compensated by advanced sensing systems and advanced robotics systems, as well as the artificial intelligence that can support these systems, said Ge. His own research at UNL focuses mainly on agricultural technology and agricultural automation sensing.

NASA works with farmers. NASA Harvest, established in 2017, is an entire subsidiary dedicated to agriculture around the world.

Ge described how the sensors he is developing can be carried on a tractor to scan the field and identify water stress, nitrogen stress, pest infestation or disease symptoms. The devices are also programmed to make data-driven decisions. “We are doing a lot of real-time imaging and developing complex models from the raw sensor readings for decision making,” he said.

An autonomous, multi-use implement is also being developed at UNL by Pitla. The prototype version of an autonomous robot named Flex-Ro was on display at the Ag4Space open house. Kunjan Theo Joseph, who graduated from UNL with a degree in biosystems engineering and is working in Pitla’s research laboratory, demonstrated how the robot can either be self-driving or guided manually with a joystick remote control.

Flex-Ro has four-wheel drive capability, and hydraulics run the wheels. Electric motors engage the navigation mechanisms, which can switch between four-wheel and two-wheel steering for tighter turns. With a 60-horsepower engine, Flex-Ro is much smaller than farm implements typically used in fields on planet Earth. Joseph said the idea is to have a swarm of smaller robots in space rather than one large tractor.

“Flex-Ro is a platform for a whole host of equipment. It can do a variety of tasks and is customizable, whereas a tractor can do maybe one specific task,” Joseph said.

So far, Flex-Ro has planted a five-acre, no-till field with a specially designed two-row planter attached underneath the robot. The planter unit has 360-degree rotation, congruent with the precise steering of Flex-Ro.

Developing new technology such as autonomous equipment and gaining a better understanding of plant growth will be valuable in the future to farm in distant galaxies, but in the meantime the information can be applied to grow better crops here on Earth.

“We have a lot of problems facing us today—an aging population of growers, degradation of the soil and water resources. A lot of the technology we can develop along the way will also help us address those critical problems on Earth for agriculture,” Ge said.

Much more research needs to be done before plants can be successfully grown in space. Ge said SPACE2 had applied for a two-year, internal grant opportunity called the Grand Challenge Initiative, part of UNL’s commitment of $40 million to fund “grand challenges research efforts.” SPACE2 utilized that funding for planning and outreach to other universities and industries already in the research field, including companies such as SpaceX, Virgin Galactic and Honeybee Robotics.

The scientists from NASA are studying the landscape closely. But they aren’t viewing a satel…

The group is hoping to receive another round of funding after applying for a new grant this spring. Now that an initial plan has been mapped out, the investment would go toward research projects, student training and networking activities. They will know if they receive funding later this summer.

While UNL is just setting up its launch pad in anticipation of advancing research in the space industry, elementary and high school teachers from across Nebraska have been involved in aerospace-related education since 1991 through the NASA Nebraska Space Grant. Elizabeth Dunn became involved with the program as a classroom teacher; she is now the youth development extension educator at Nebraska Extension in Otoe County.

Through the NE Space Grant, Dunn trains teachers as a Nebraska Space Ambassador. She sees the value in outreach activities to youth, such as Ag4Space.

“Agriculture in space is definitely a job most people don’t think about. Ag4Space blends something that is homegrown and normal to us with something that is so extraordinary, almost mythical,” she said. “Students and young adults can realize they have a place in agriculture but also space.”

A new era in the space race has begun, one that is inspiring agriculturists, engineers and scientists to explore new fields together. As Keshwani said, “The idea of planting the first acre of corn on the moon or Mars really gets the imagination going.”

Farmers of the future will be looking to infinity and beyond to find their place in space. Forget about doing a rain dance—start practicing your moon walk.

Reporter Kristen Sindelar has loved agriculture her entire life, coming from a diversified farm with three generations working side-by-side in northeastern Nebraska. Reach her at Kristen.Sindelar@midwestmessenger.com.